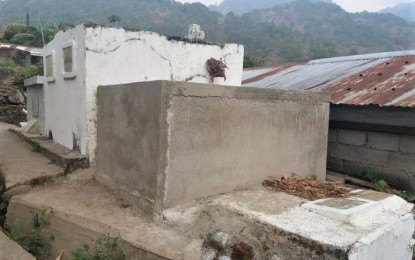

BURIAL PRACTICE. Tombs can be seen beside houses where people actually reside. The culture is an ancient practice observed by people in Benguet and the Cordillera region. (PNA file photo by Liza T. Agoot)

LA TRINIDAD, Benguet -- Cemeteries have been established in the towns but residents in this vegetable-producing province still observe the culture of burying their dead very close to them -- usually at the backyard of their houses.

"Closely-knit kasi ang mga tao sa Benguet. Inililibing sa katabi lang para mas close sila sa namatay (People of Benguet are closely-knit that is why they bury their dead near their house)," said Camilo Alumit, Executive Assistant of Governor Melchor Diclas.

Aside from being a native of Benguet, Alumit also served as a tourism officer of Kabayan town and as a municipal councilor in charge of tourism and culture. He later joined the provincial tourism office.

Kabayan is known for its unique traditional practice of burying the dead which include mummification that was observed in the olden times.

He said his parents were both buried very close to their family residence, in their backyard in Kabayan.

He said when he wanted the same when his time comes.

“The entire province still have it [the practice of burying the dead in the residential compound] even if there are already cemeteries, especially if gusto nila mas malapit sa namatay (especially if they want to be closer to the one who passed away),” Alumit said.

He said there used to be a public cemetery in Kabayan but after the strong earthquake struck in 1990, people returned to bury their dead at their residential compound or a common family backyard.

He said the Karao tribe in Bokod, Benguet still practices burying the dead in their homes or the backyard.

“'Yun siguro ang nakagisnan nila na kultura. When I attended one burial sa Karao, sa baba ng bahay, kaya most of their houses are elevated, may poste (Maybe it was the culture they grew up with. When I attended one burial in Karao, it was under the house that is why their house has posts and are elevated),” Alumit said.

In the capital town of La Trinidad, the Laoyan-Abalos ancestral residence has a room devoted to the burial ground of their ancestors.

In an earlier interview with former La Trinidad Mayor Greg Abalos, he said in one of the rooms of the wooden structure, there is a table-like furniture that is covered with a cloth in a corner, looking like an altar of some sort, but actually bears the gravestone of their ancestors.

He said it was the desire of their ancestors to be placed in the house for them to be always there with their family.

Alumit said unlike in other places, burying the dead in the backyard does not require a special permit since it has been a native practice observed by the ancestors in the old times that continue to the present.

Burying the dead in one’s residence and the backyard is also proof of ownership of the land, he added.

Health considerations

In the past, people of Benguet do not embalm their dead as it runs counter to the tradition.

However, Alumit said with more people now educated and knowing the old practice's health risks, locals have started embalming their dead relatives.

Diclas, a medical doctor by profession, said during a press conference that burying the dead near the residence is a health risk and that bringing the dead to the cemetery is highly recommended.

Close ties seen during wake

In Benguet, a grieving family does not have to worry so much about financial needs to sustain the wake of a loved one.

Relatives, friends, members of the community and the whole neighborhood join hands and pitch-in whatever they can contribute.

Each family member has a role to play when a member of the community dies.

Some give money, others give rice, agricultural products or pigs to be butchered, others contribute their time by helping cook, while some help in the vigil by singing or beating the gong.

Such contribution given by one will be later on be remunerated by the relatives when the others also lose a family member, making the tradition of helping and “bayanihan” live on in the present and in the years to come.

No metal nails on caskets

Aside from the practice of burying near the house, Benguet locals, especially those who come from well-off families, still observe the non-use of metal nails for caskets.

Alumit said according to tradition, nails rust and contaminate the corpse, causing misfortune or illness to the family members who are still alive.

In the Ilocano dialect, he said “there are times when a family member dreams of the corpse asking for help because of the discomfort or the dead telling the relative in the dream that it is feeling cold and is dirty, or a living family member suffers from unexplained illness, the family decides to open up the grave and there they will see rusts or water seeping in.

Such opening will mean an actual wake again happening and going through a ritual before it will again be buried.

He said for rich people who maintain a living tree for future purpose, a whole trunk may be used as a casket.

For others, putting together pine wood to make a casket will suffice, but such has to be nail-free.

Alumit said: “If I die, I want my remains to be brought home so that I can have that nice pinewood casket which is proof of the people’s love for me, contributing for wood and supplies needed during my wake. (PNA)