MANILA – "I did not become President to preside over the death of the Philippine Republic."

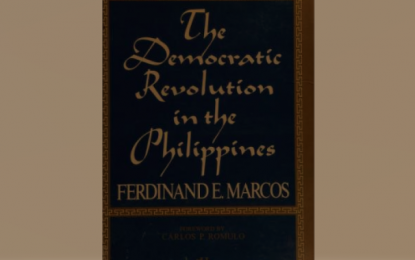

This was how the late former President Ferdinand E. Marcos Sr. began the first paragraph of Chapter 5 of his 45-year-old book "The Democratic Revolution in the Philippines" (Third Edition) published by the Marcos Foundation Inc.

In the second paragraph of the same chapter, subtitled "The Hour of Decision," Marcos wrote: "This much was my resolution when the last word of 'Today's Revolution: Democracy' was written on Sept. 7, 1971. At that time, I had already suspended the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus in some parts of the country. One year and fourteen days later, I signed the proclamation (No. 1081) placing the entire Philippines under martial law."

He explained that the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus was necessitated by the bombing of the rally of leading Liberal Party candidates at Plaza Miranda in Manila on the night of Aug. 21, 1971. The suspension of the writ was lifted on Jan. 7, 1972.

According to Marcos, the sequence of events "might very well suggest to the reader that I had been deliberating over the martial-law decision for more than a year. There is an element of truth in this. But until the evening of Sunday, Sept. 17, 1972, I continued to hope that we could proceed toward change and reform and realize in modest measure a Democratic Revolution, without having to accept the martial necessity."

"On that long night (9/17/1972), I sat alone in the private study of Malacañang, the presidential residence, contemplating one document that stood out among the mass of papers on my desk. This was an extraordinary document because it was spurious. In earlier, less troubled times, it would have been dismissed quickly as a cheap and ludicrous political stunt. But within the context of the national condition and taken together with other documents, it revealed to me the reality and the scope of the danger to the Republic of the Philippines."

The 416-page book, actually comprising three parts, documented Marcos' aims and plans for creating a New Society for the Filipino people "without bloodshed and without crippling, much less eliminating, civil government" under martial law as authorized by the Philippine Constitution with certain safeguards in a system accomplished with the consent of the governed through a referendum.

In the preface for the Second Edition of the book, Marcos said on Sept. 21, 1972, in accord "with a provision of our Constitution, I proclaimed martial law throughout the Philippines as a final recourse to combat two principal sources of grave danger to society and the government-- a rebellion mounted by a strange conspiracy of leftist and rightist radicals, and a secessionist movement supported by foreign parties."

He added: "Martial law, together with the New Society that has emerged from its reform, is in fact a revolution of the poor, for it is aimed at protecting the individual, helpless until then, from the power of the oligarchs. Martial law was therefore a blow struck in the name of human rights."

In the Third Edition published in 1977, Marcos cited a number of critical documents and dangerous happenings in various parts of the country that prompted him to sign Proclamation No. 1081 on Sept. 21, 1972, although it was officially announced two days later.

The documents included reports "naming places, dates and occasions of meetings between insurgents and persons in high and strategic places, in politics, industry and media; of secret meetings among retired generals; of money used to support any student demonstrations so long as they were disruptive; of any assignations with radical leaders in metropolitan Manila; of foreign nationals engaged for the dastardly work of assassination; of high-powered arms smuggled into our shores."

There were also reports about an alleged plot to assassinate the President and of big-time kidnappings and robberies not only in Manila but also in the other centers of populations in the country.

Among the destructive and dangerous events cited were the riotous demonstrations of radical students and laborers in Manila in January 1970; the Plaza Miranda bombing of Aug. 21, 1971; the so-called "Digoyo" incident involving the "M/V Karagatan," a ship that had come from overseas and landed about 3,500 high-powered firearms with corresponding ammunition in the village of Digoyo in Palanan, Isabela.

Meanwhile, in a 14-page foreword for the Marcos book, Gen. Carlos P. Romulo, former president of the United Nations General Assembly, long-time secretary of Foreign Affairs, president of the University of the Philippines, National Artist for Literature, and Pulitzer Prize winner, said in part:

"Foreign observers watched the conditions of the times (in the Philippines) with critical pessimism. They more or less agreed with the observations of Time Magazine (October 21, 1966):

"......Behind broad Roxas Boulevard. where young hotrodders zigzag furiously, is one of Manila's commercial centers: boutiques, which attract American wives all the way from Hong Kong, stand side by side with gun shops that sell everything from matchbox-size pistols to automatic refiles. The Philippines' private citizenry owns more weapons (365,000) than the entire military and police forces. Nightclubs, bars, even the Supreme Court mount signs reading: "Check Your Firearms Before Entering." No self-respecting, lawless Filipino would think of complying.

"All that firepower is bound to lead to trouble, as the Philippines crime rate proves. According to the National Bureau of Investigation, crimes in the Philippines jumped ten percent in 1965. (the year Marcos was first elected president). There were 8,750 murders (many times more than in New York), 5,000 rapes and 7,619 robberies.

"What made criminal conditions worse, however, was the connivance of the police and many politicians with criminal elements. For a variety of reasons, policemen, who were otherwise sworn to uphold and enforce the law, were largely no better than the criminals. Politicians, on the other hand, maintained private armies ostensibly for "personal security," but during elections, these private armies were employed against opponents and the peaceful population as well.

"The Philippine press, the 'liveliest and freest in the world' denounced this state of affairs, but the press itself, owned by the so-called "oligarchs," was used to defend the social order which spawned and encouraged these very conditions. (more)

"This essay on democracy and revolution was written at the height of crisis, 'at the barricades' so to speak, when President Ferdinand E. Marcos had to make quick, and as it turned out, far-reaching decisions.

"This book, therefore, reveals the man behind the martial-law situation in the Philippines. This situation has been called by friends a 'smiling martial law,' for it is led and managed by a man who insists on the subordination of the military to the civilian power. Only Marcos on the entire spectrum of Philippine leadership could have done this.

"Finally, this book reveals the man and his times. It was written by a leader who knew how it felt to be 'sitting, along with his people, on the top of a social volcano.' It was written as a cautionary essay; to explain the demands of the times and to warn the people of the dangers ahead of them. The country, in 1971, was on an inexorable march towards destruction.

"Ferdinand E. Marcos was destined to stop it." (PNA)